Still Life

We can never fully comprehend the inner pain and suffering of others.

Reza Baharvand

Construction and Destruction in the Large Frame

1. In the Ghent Museum of Art there is a still life painting by Willem Claesz Heda in the foreground of which we see messy artwork tables with half-eaten cakes, peeled lemons, and collapsed wine glasses. In the background, there is a palace that stands firm and solid bearing absolutely no sign of damage. This 17th-century still life is in total contrast to Reza Baharvand’s latest body of works.

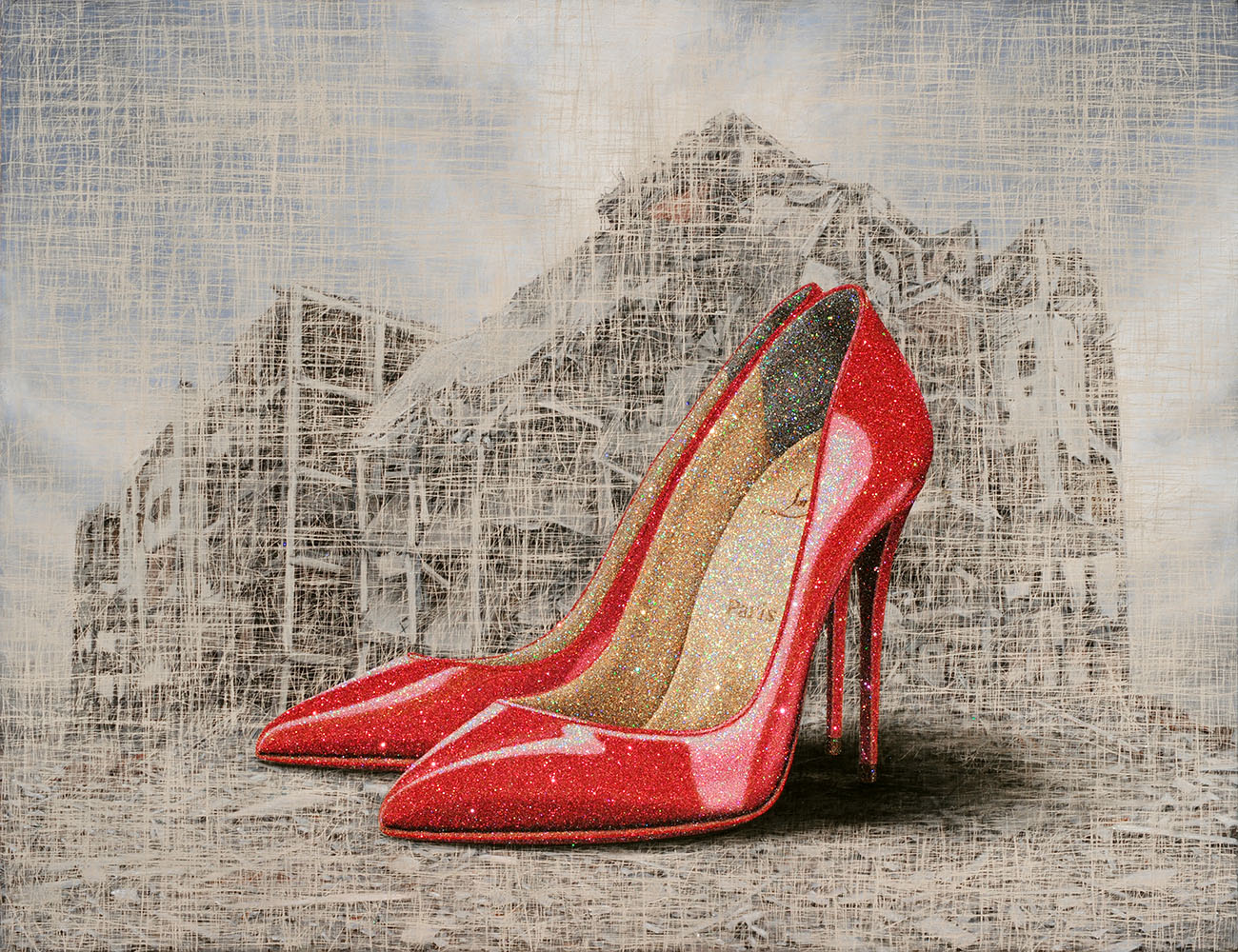

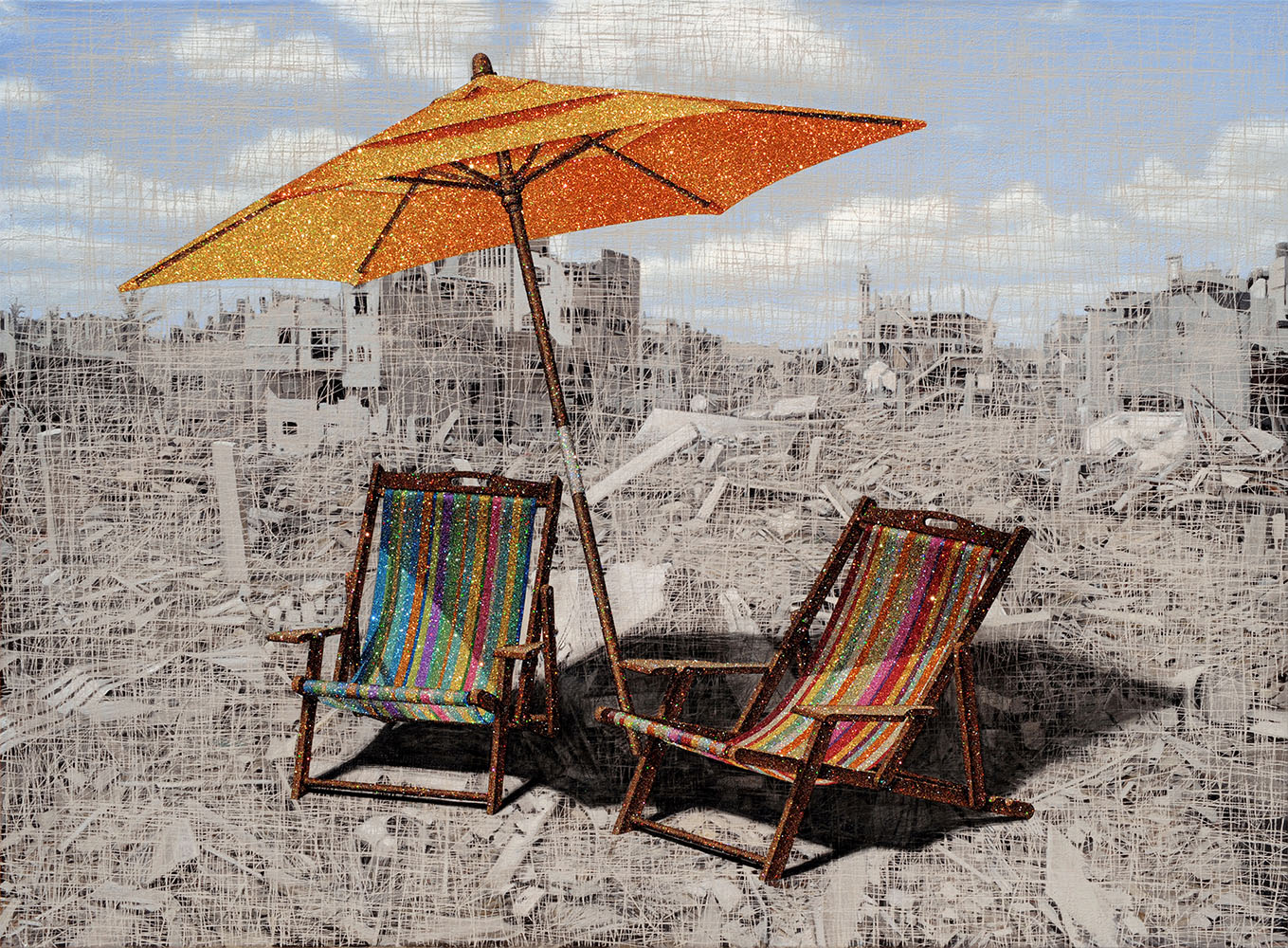

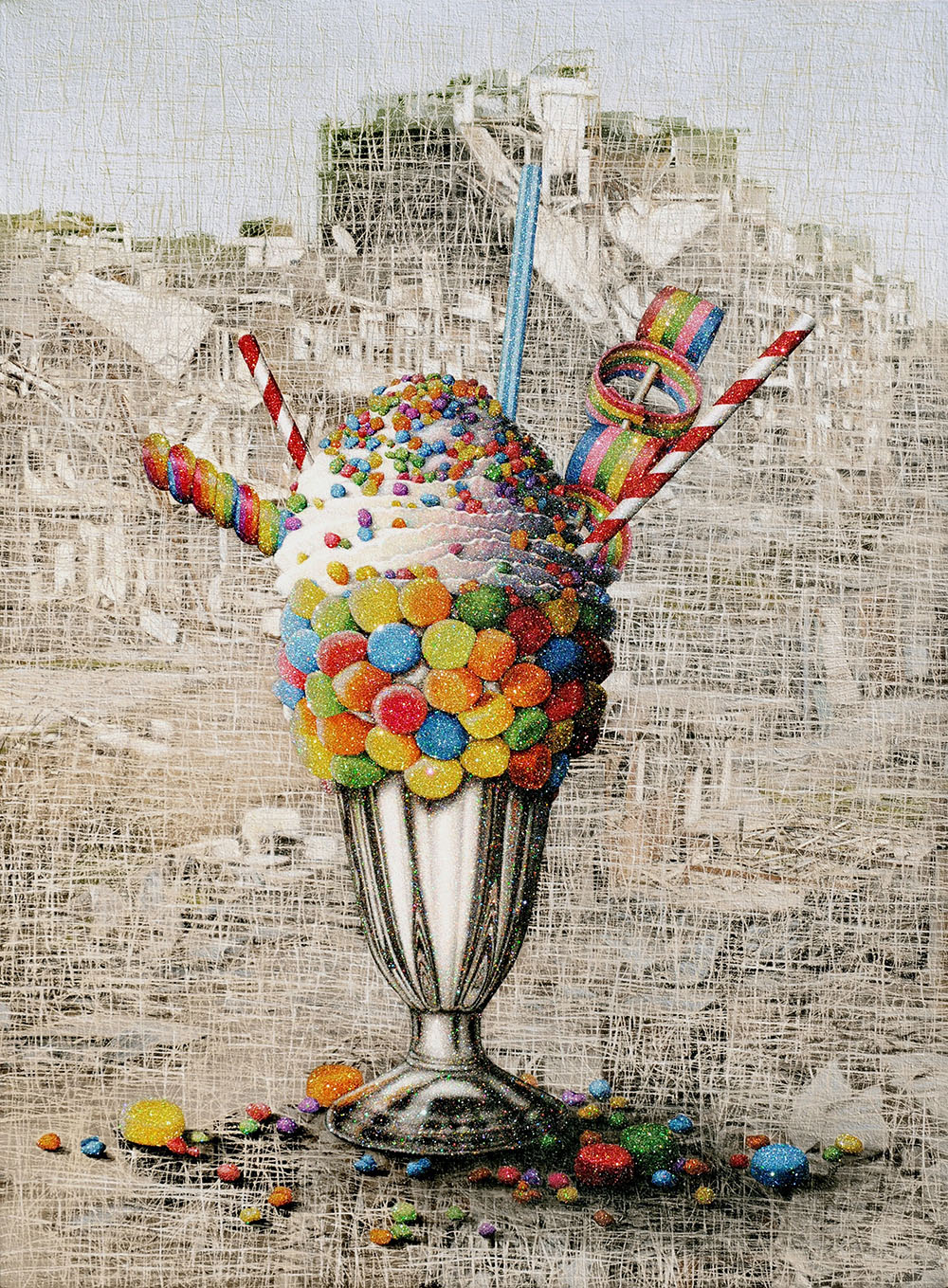

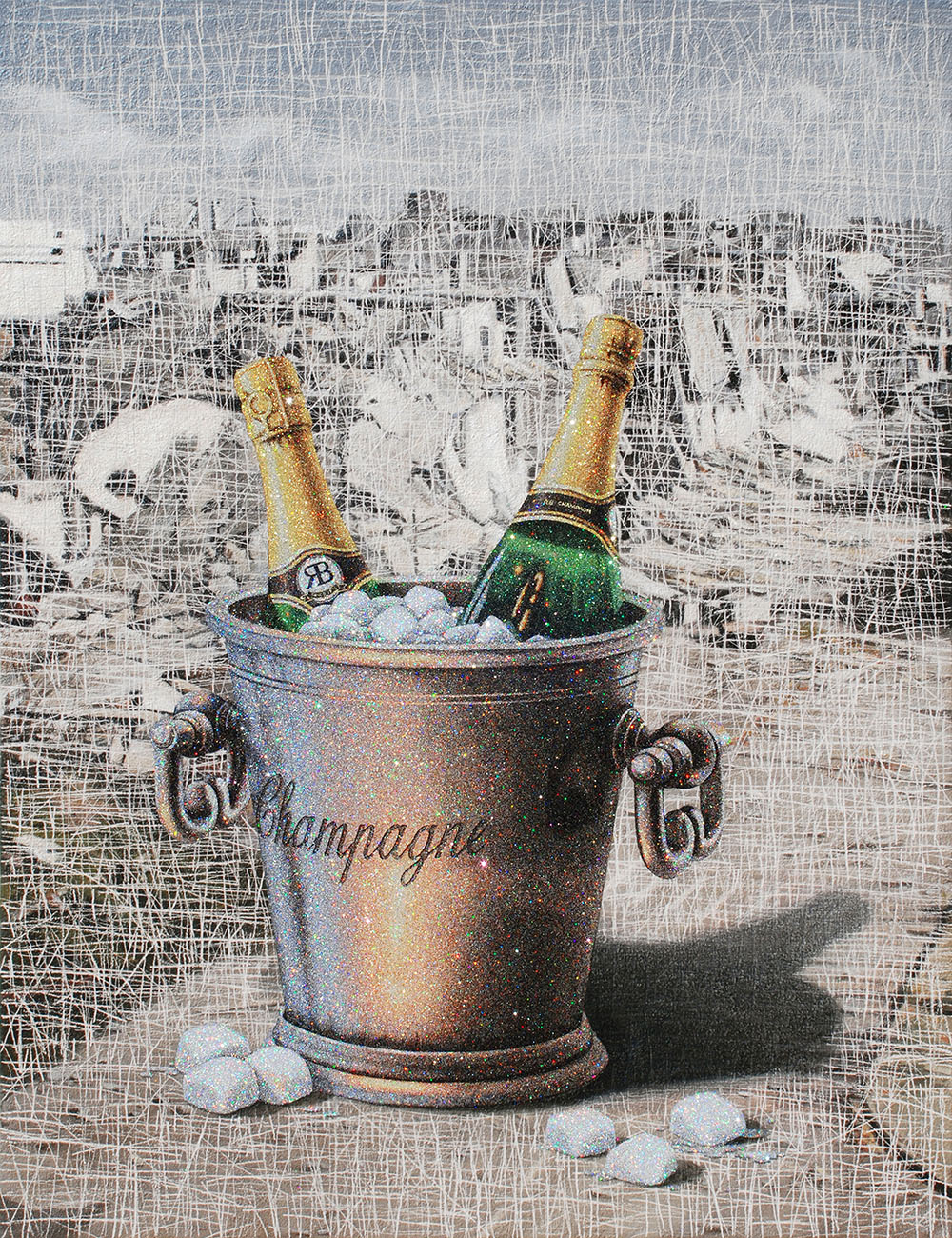

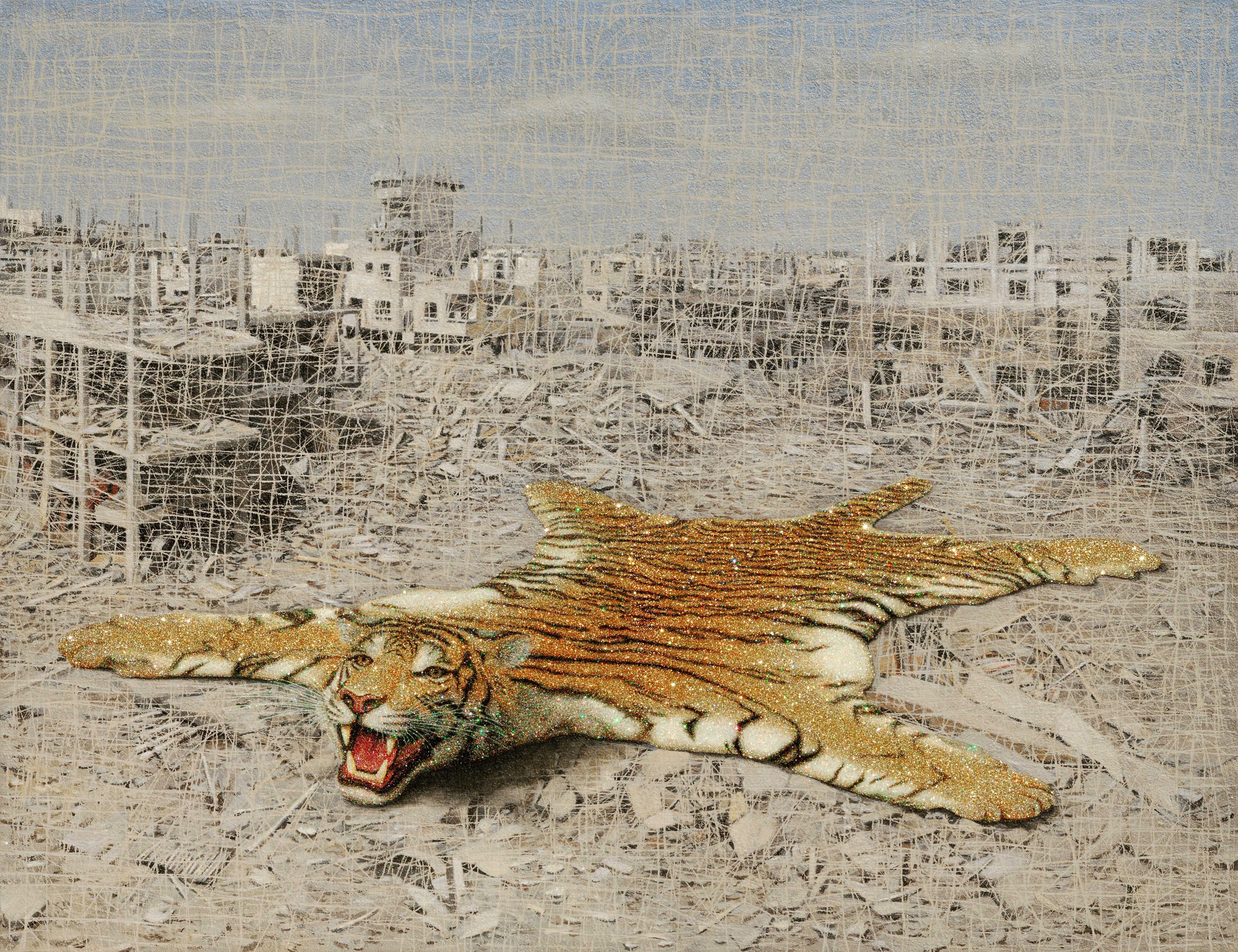

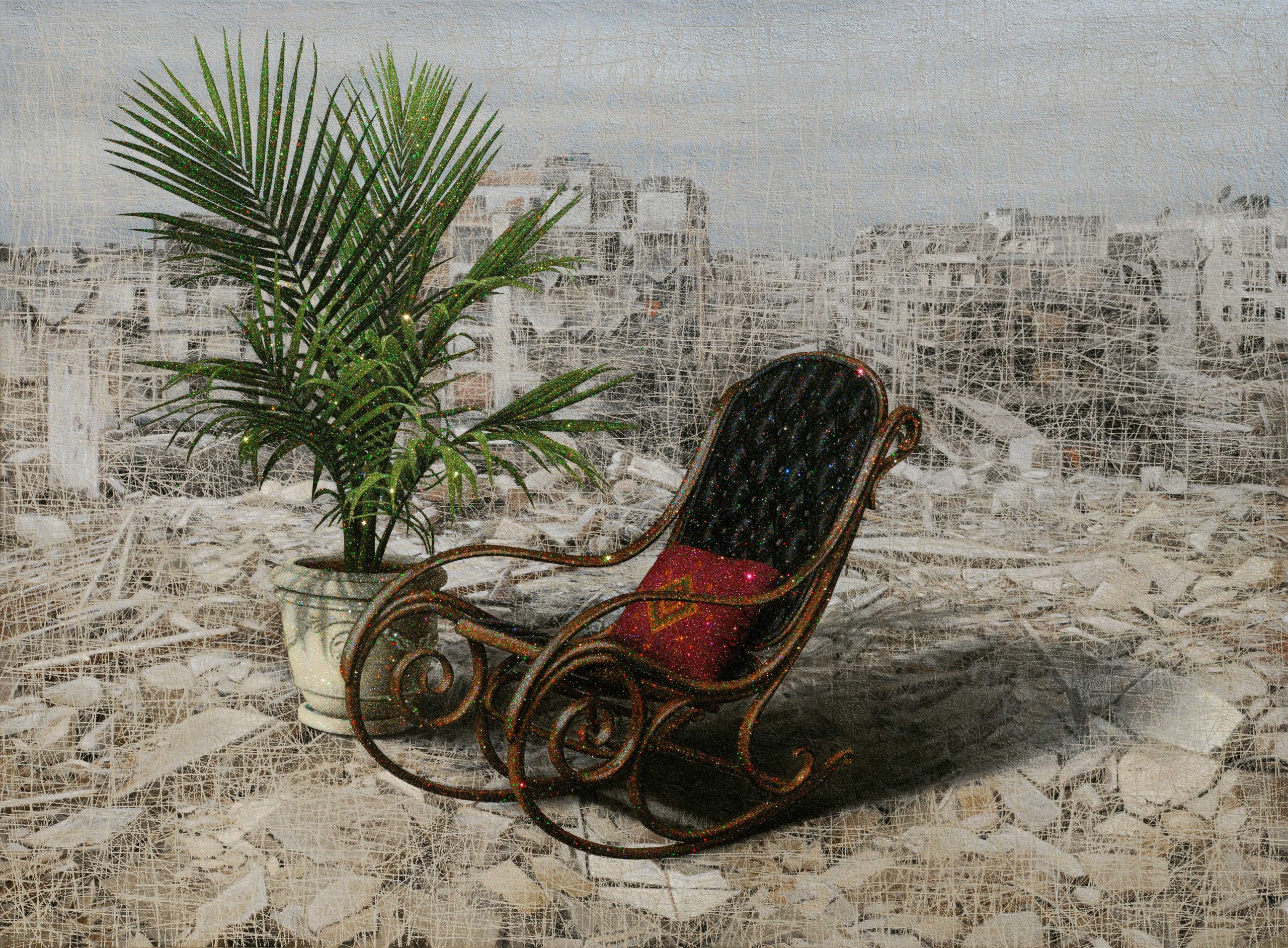

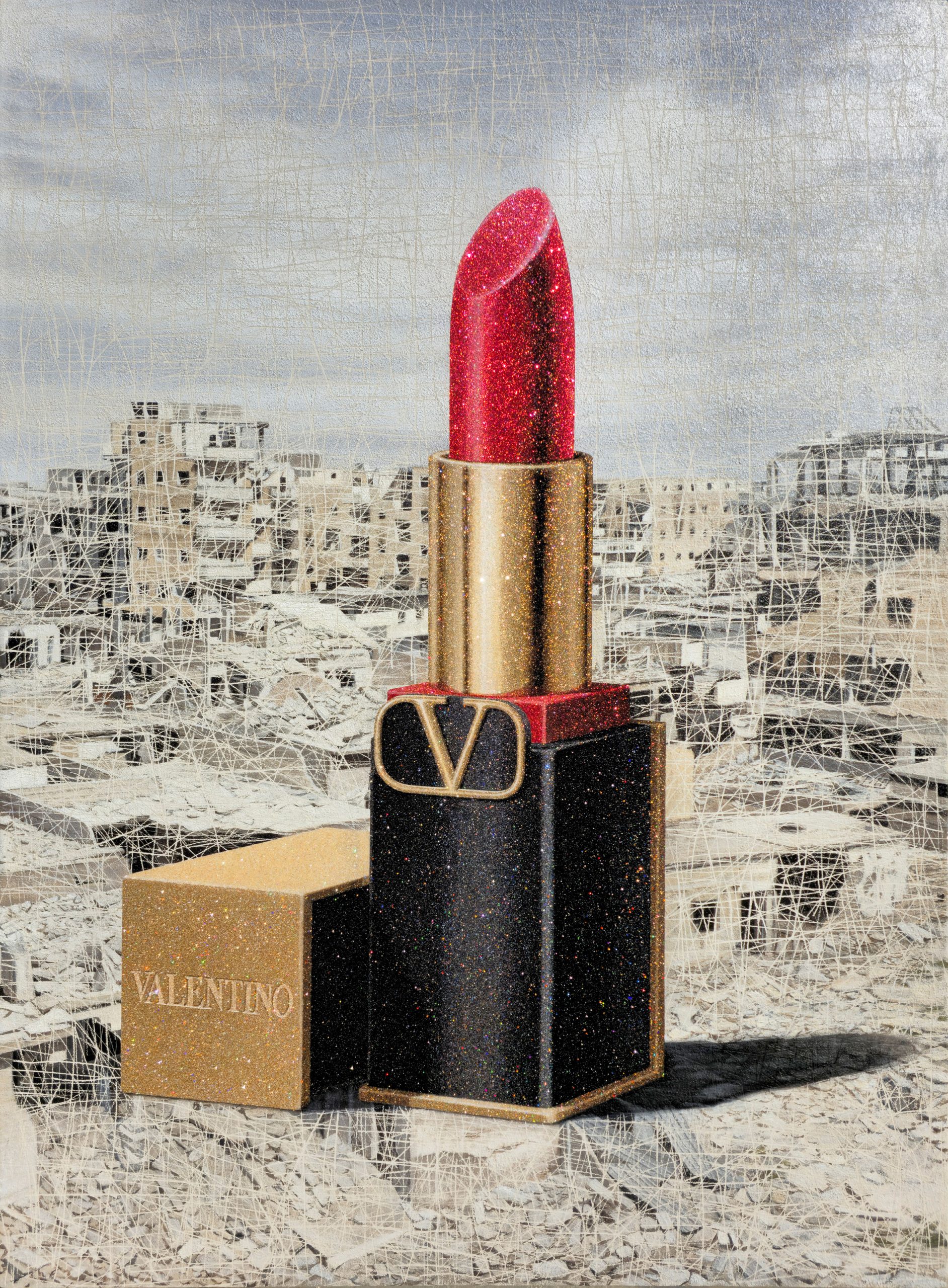

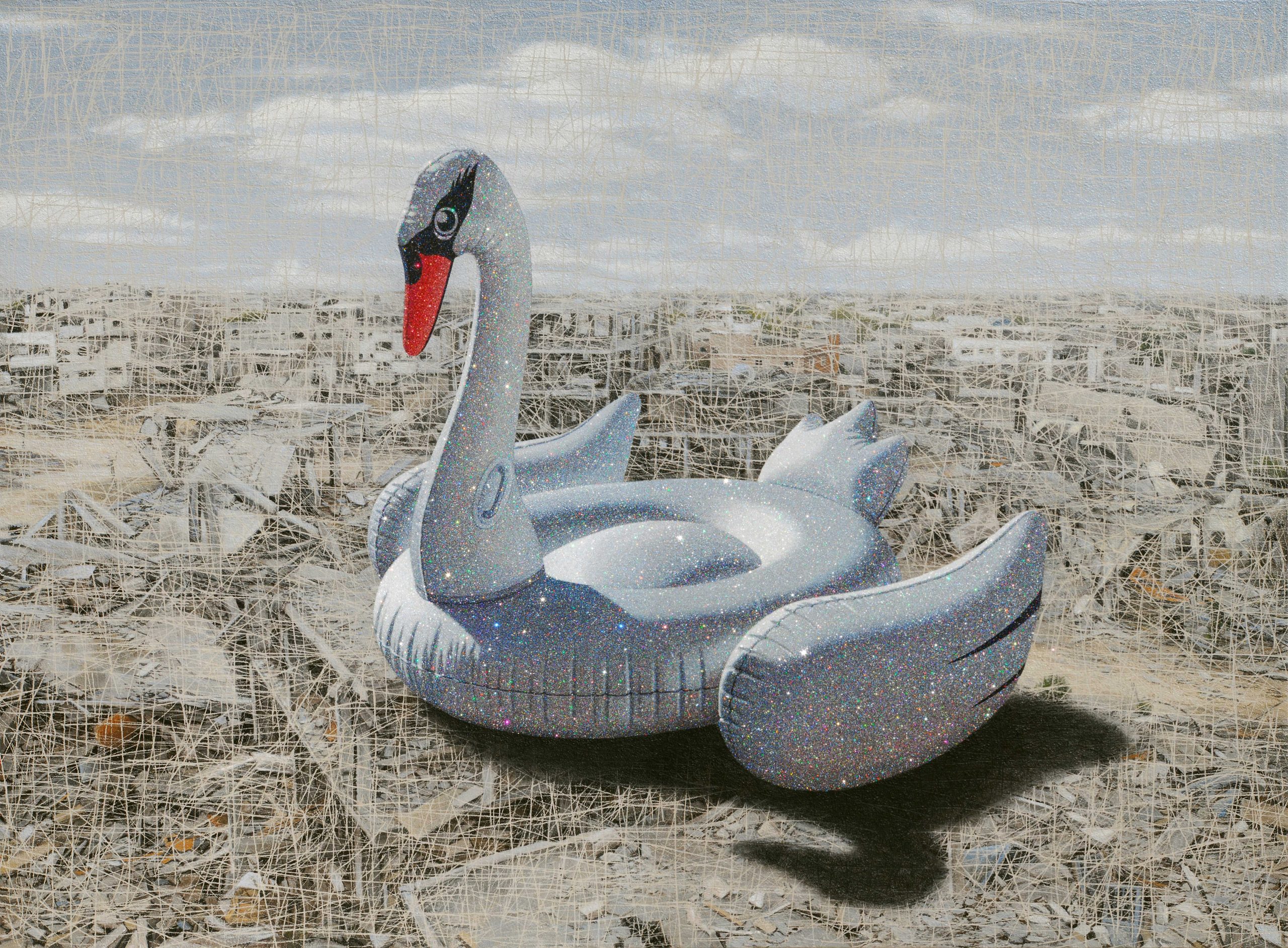

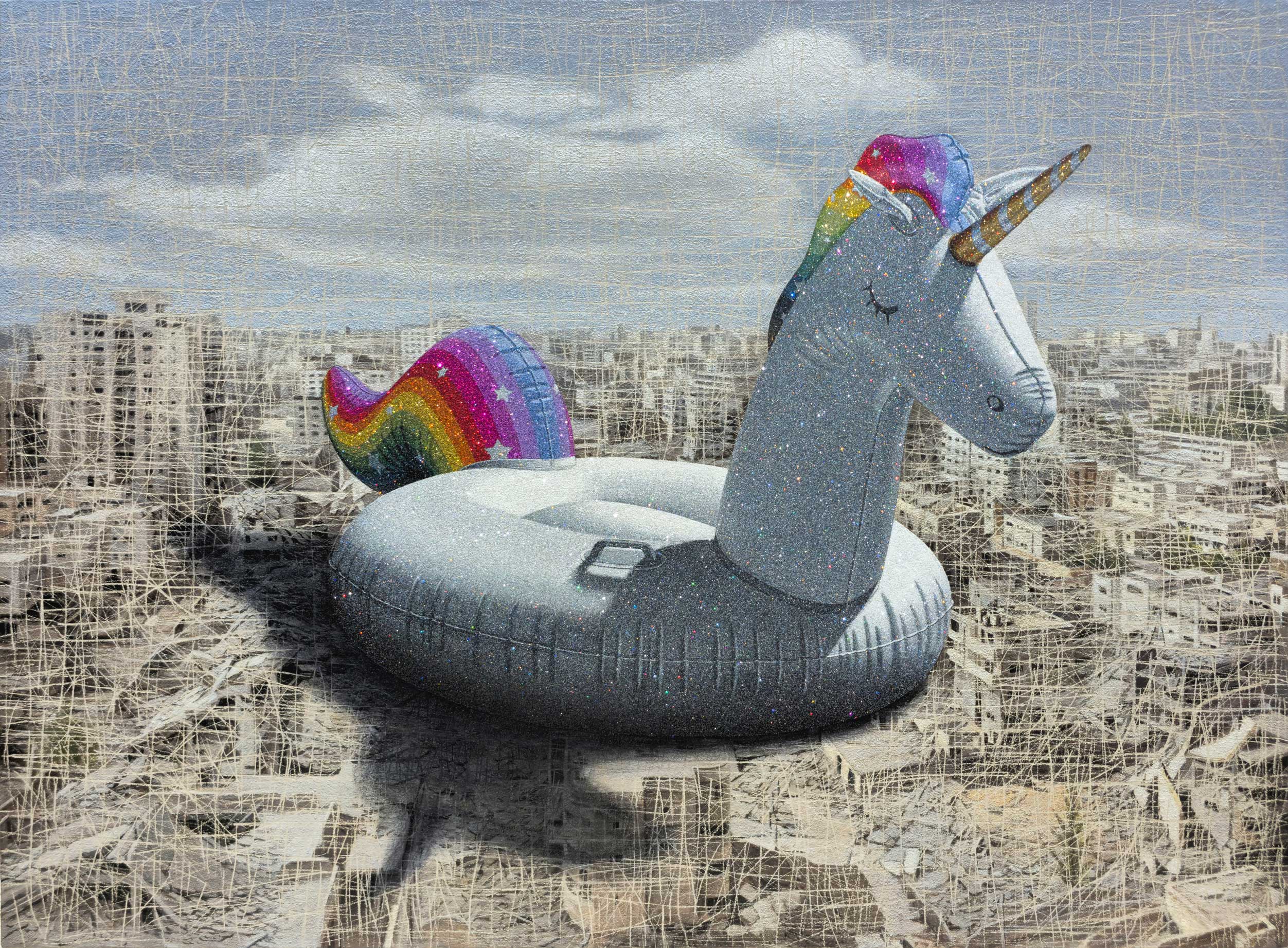

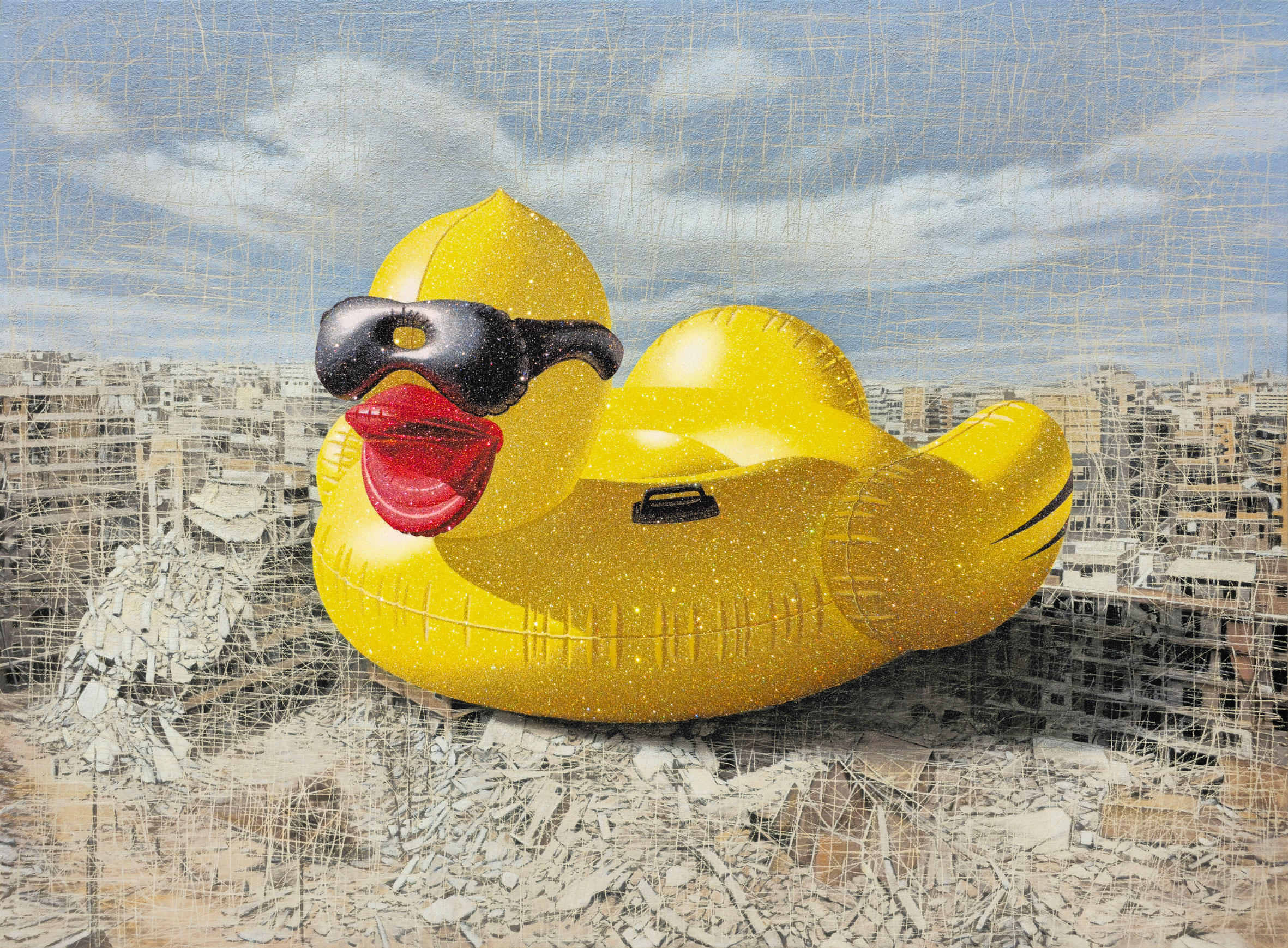

Unlike the Dutch still life, objects offered to the viewer in Baharvand’s foregrounds are associated with a luxurious lifestyle. They are not only intact and completely safe from damage, but they have also been gilded for a brighter and more eye-catching appearance, similar to objects spotlighted in store windows. In contrast to this artificial and showcased space, we are faced with ruins in the background: War-stricken urban areas that have been constructed with great care and obsession only to be mercilessly destroyed by their maker.

In the Dutch still life, in order to show the ephemeral nature of life, objects such as skulls, half-finished wine glasses, and sand clocks are portrayed in the foreground making the viewer sense his own immediacy to life’s transit nature. In Baharvand’s works, proximity to ruin has given way to distance from it. The ruin is in the background where it casts its spell on the objects before it. With this change in the arrangement of things, the painter has defamiliarized the well-known order found in still life paintings.

2. Man is generally absent in still life and when not totally absent, he has an indirect presence. In Baharvan’s work, the objects in the foreground convey man’s sense of relief from the ruin in the background. Man is absent too however his indirect presence is traceable through the ruins in the distance and the gilded work in the front.

3. Still life is a set of everyday objects within a small frame. Baharvand’s works are totally devoid of such an arrangement of everyday objects. In each painting, a single object represents a luxurious lifestyle, with its glitz and glamour reinforced by the glittering material applied by the painter. Moreover, in this series, huge canvasses replace the traditionally small still life canvas. The viewer faces a large object that attempts to mask the ruins in the background. Nevertheless, the ruin is not masked but rather accentuated.

“Destruction” is the central theme of Baharvand’s present body of works. He constructs and destroys, and to further highlight the “destruction” he puts an object before the viewer and displays creation and destruction next to each other.

Dr. Amir Nasri

The splendor of the Ruins

The idea of ruin and destruction being splendid and breathtaking in a positive sense troubles the subjective basis of ethics and the very foundation of human values. It is with this idea in mind that the paintings of Reza Baharvand call to mind Jacques Derrida’s Deconstruction. In this Weltanschauung, destruction is simultaneous with reconstruction and rebuilding. In other words, what appears as a pictorial emergence in a work of art, or the platform for a comely subject, is the result of splendid destruction which is difficult to distinguish from the reconstruction of the piece, or to identify the primacy of either one. Behind all the pieces of the collection, Baharvand has pictured ruined urban spaces that looked different not long ago. The background is accurately and realistically created and then, deliberately corrupted and disintegrated. In other words, he adds ruin upon ruin. But what comes into our view in the anterior or the foreground of his work, according to poststructuralist philosophers, is “the removal of the veil”, i.e. the removal of veil from a bitter truth from the war and from the world that has deeply affected the artist pushing him to create this works. Adorned lit chandeliers, scattered balls, shiny shoes and sumptuous thrones drained of the meaning of rest and leisure are the consequence of this removal of the veil which the artist has envisioned. In fact, in all the pieces, pondering the critical contrast witnessed between the background and the foreground, both in form and theme, draws us closer to Reza Baharvand’s worldview as created in this collection.

Shahrooz Mohajer